On 18th July 2017, 35 refugees in Moria camp on Lesvos were arrested. The arrests followed a two day protest involving a sit- in outside of the European Asylum Support Office inside the camp and a demonstration. The protesters were holding banners denouncing dehumanizing conditions in the camp, and calling for freedom of movement for those kept on the island. Images and videos of the police using excessive violence against the protesters reached both international media and social media.

Moria refugee camp is known for its appalling conditions and overcrowding. Initially built for 3000 people, it is currently hosting about 6500. The living conditions in the camp have been heavily criticised by human rights organisations. Last month, a 26-year-old Syrian refugee was hospitalised after setting himself on fire at Moria in protest after having had his application for asylum rejected a second time.

Following the protest, there were clashes with the police. A few hours later, the police carried out raids on the camp and made 35 arrests. Many of the arrested were not even present at the protests, yet alone the clashes. The arrestees report being subjected to brutal beatings by the police during raids while in custody, with one person hospitalised for over a week and many needing medical attention due to police brutality. The observers concluded that the arrests were arbitrary, and people were targeted because of their race, nationality, and location within the camp. 11 people filed official complaints for their treatment by the police.

On 23rd April, the Moria 35 trial started at the court of Chios. The arrested stood accused of participating in clashes with the police. Nobody was charged individually, instead the Greek state opted for charging the whole group together. Here are some notes from the Moria 35 trial from a person involved in defence of the accused.

The first striking observation was seeing 35 black people as defendants, while everyone around them was white. It was like a punch in the stomach. There were so many cops, lots of undercover too, it was like the defendants are the worst people on Earth. Everybody entering the court was thoroughly searched. The prohibition on cameras, videos and photos was enforced. A female juror asked to be excluded from the trial, citing “ideological reasons”. We all knew what that means.

The judge was aggressive sometimes. She appeared not to be able to organise the whole thing, with all the defendants needing translations into different languages and the general mess of having 35 people in the docks. Also, we knew this judge from previous refugee trials and we didn’t think she is fair. She repeatedly asked the translators to make sure the defendants know that they have “destroyed property of the Greek state and attacked policemen”.

The trial begun with police witnesses testimonies. All but one did not recognise a single defendant as a participant in the clashes. They stated that they are unable to do this due to the vast numbers of people living in the camp and that it was hard to know who did and did not take part in protests. The defence lawyers asked them to disclose in what actions exactly each of the defendants allegedly took part in and how come they are unable to recognise at least some.

The first witness was the police chief of the squad which participated in the clashes. He described how he saw the events. He also admitted that the arrests were carried out by another group of cops, and not the one who took part in clashes. He did not recognise any of the defendants as the people participating in the protest. While asked who actually got arrested, he responded: “Those who were near or did not get away!” Basically, they just grabbed random people and put them on trial.

The second witness, a firefighter, testified that he intervened to extinguish the fire in the camp’s olive grove. According to his testimony, he saw someone who came out of the camp, who stumbled as he proceeded, and, after a some time, flames appeared on the grass. The witness testified that he saw the three perpetrators and when asked to point them, he said they were the last three left in the last seat. But the persons he pointed at were different from the persons he singled out in his written testimony. The audience laughed at this apparent inability to recognise the defendants. What’s more, the firefighter could not explain how come the people he pointed in his preliminary statement were at the police station a mere 20 minutes after the incident the witness described. The third police witness also did not recognise among the defendants a single one of the alleged perpetrators.

In summary, out of 7 prosecution witnesses (6 cops and one firefighter), none were able to clearly recognise any of the defendants from the day of the events. There were also other inconsistencies in the witness statements. They could not agree on the number of police involved, or how much violence there was. One witness, when asked who did the police arrest, stated that they “arrested the people on the front, or whomever they could”.

There were 8 defence witnesses: refugees, NGO workers, and people in solidarity with the refugees. Their statements were consistent: all provided the same timing of events, all stated that the police arrived when the situation already calmed down and that they grabbed whomever they could: without any evidence. Only one saw the refugees throwing stones, but also the police doing so.

Five defendants gave their testimony. All of them were arrested when the situation was calm. All were arrested inside or right outside of their containers in the camp. Some of them weren’t even at the peaceful sit- in protest earlier in the day. One saw the police throwing tear gas at people when they held a peaceful march. One recalled that the police told them to go back to their containers, which they did: only to get arrested a few hours later. Three of the refugees spoke about extreme police violence: including stepping at people’s necks, spitting right on their faces, and one broken arm.

The court verdict was delivered last Friday afternoon. Despite of insufficient evidence, 32 out of the total of 35 defendants were found guilty of committing, or attempting to commit, grievous bodily harm, to 24 police officers. They were sentenced to a total of 26 months imprisonment suspended for three years. Fortunately, they were also granted the right to appeal. Three people were found not guilty.

The Moria case is an example of how the refugees are treated in Greece, and the whole of Europe for that matter. They are provided with appealing living conditions, are contained to designated places, often face racism and mistreatment from the authorities. When they rebel, the state is easy on inflicting collective punishment on them. The trial of 35 makes it clear once again how much repression is at the core of refugee policy, but also how crucial it is to organize resistance and solidarity to give visibility and voice of all prisoners in the refugee camps of shame – an embarrassment of administrative arbitrariness, police violence and mass retaliation.

Due to the appealing treatment of refugees in Moria camp, another riot broke among the camp residents at the beginning of April. The riot resulted in the destruction of the camp’s medical centre.

zb

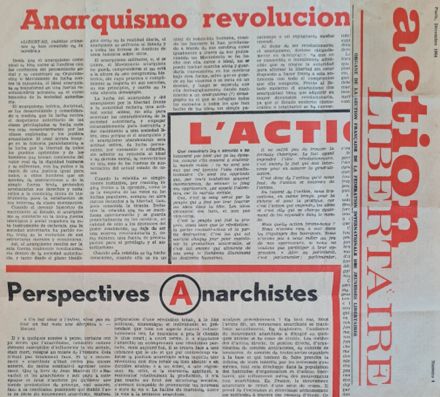

Photo: NoBorders/Arash Hampay