Government’s adviser on “political violence and disruption” demonstrates how the British state machinery perceives the left in general and anarchists in particular

On 21 May, just before news of the election swept the board, the British government’s adviser on “political violence and disruption”, Lord Walney, submitted a 291-page report to Parliament in which he attacked a number of political movements and demanded extra powers for the police. “Lord Walney” is John Woodcock, a former right-wing Labour MP who quit following sexual harassment allegations, and who has worked alongside his advisor role as an active lobbyist for the fossil fuel interests, Israel and the arms industry. Despite it taking three years to produce his report, with regular leaks to the right-wing press every time the Tories wanted to stoke up more anger over “disruptive protests”, few of its 41 recommendations made it into the Conservative election pledges (and none into Labour’s manifesto).

So why bother with it? There are two reasons. The first is that Woodcock’s report is revealing about the way the machinery of the British state perceives the left in general and anarchists in particular, and the relative fragility of the parliamentary system. The second is that whoever is in government over the next five years is likely to face more and more disruptive protests. Woodcock’s work, fundamentally a call for expanding police surveillance, may have little immediate traction, but it may yet influence repression.

The report, “Protecting our Democracy from Coercion” discounts the most significant threats to democracy in Britain: corporate dark money, systematic misinformation by a fanatical right-wing press, and the antics of parliamentarians themselves (most notably Boris Johnson, the sponsor of Woodcock’s peerage, partying in Downing Street as thousands died during the pandemic). Instead, for Lord Walney what democracy needs defending from most is “extreme political activists” who have “little traction with voters and cannot secure real electoral support” and so “attach themselves to causes that parts of the public are concerned about”.

While his report accepts the very real, documented violence of neo-Nazi groups, Woodcock nevertheless insists that “too little attention has been paid to serious forms of violence, intimidation, and incitement of hatred on the extreme left”. The report’s real motivation is to force more punitive state action against the left – noting five prominent campaigns, from environmental direct action to Black Lives Matter, which reads like a list of political causes he opposes personally. A former chair of Labour Friends of Israel, Woodcock reserves particular ire for Palestine solidarity groups, alleging without evidence that their protests are “accompanied by violence and antisemitic incitement with little police action”. This is simply untrue, as Netpol’s recent report on the policing of demonstrations since October 2023 extensively documents.

Woodcock’s analysis—and there are pages and pages of it—shows little real knowledge or understanding of the size, significance, influence or fundamental differences between the individual groups he mentions. He views all as fitting within an inherently dangerous “Far Left subculture” because they express a broadly “anti-capitalist outlook”. In doing so he adopts the same paranoid approach to protest groups often mirrored in police intelligence gathering on protesters, which means everyone who isn’t respectfully (and often ineffectively) lobbying parliament is seen as a potential threat to public order, no matter how large or small they are.

Central to Woodcock’s argument is his belief that political legitimacy derives solely from “the primacy of the will of the British people expressed in democratic elections”. He rejects campaigners who “compare themselves favourably to previous generations of civil rights protestors” by insisting that, unlike the past, nowadays “liberal democracy and open channels of information give people the agency to secure societal change”.

Never mind that the “will of the people” is never fixed, that the media is prone to marginalising dissent by amplifying controversy or that polling shows public trust and confidence in Britain’s system of politics and elections is at a record low. Woodcock insists that anyone breaking the law resisting, for example, the government’s terrifying inaction on the immediacy of the climate crisis, at a time when scientists are literally begging all political parties to take more ambitious action, is simply trying to “impose their views on the rest of society without the democratic consent of the people”.

What is fascinating is the way the report goes on to identify “anarchist analysis of society and ways of organising” as a common thread through so many of the protest movements it criticises – implying anarchist ideas are, rather hopefully, everywhere. This provides an excuse, of course, for Woodcock to criticise militant anti-fascism and practical solidarity with the Kurdish struggle, but often the anarchist ways of organising he fears are simply the mutual aid, decentralised structures and a rejection of hierarchies that these groups practice. He just cannot comprehend not having someone in charge to keep everyone in line and is also equally frustrated with anarchists’ focus on anti-systemic practice and a refusal to put forward a programme of policy-demands on the state. This, he says “makes this form of activism particularly difficult to reconcile within a democracy”.

What Woodcock is equally loath to acknowledge is the other more obvious common thread that links all these movements – police violence and state repression. It motivated Black Lives Matter in 2020 and the Kill The Bill movement in 2021, while a greater awareness of intrusive police surveillance (not least from the spycops scandal and ongoing Undercover Policing Inquiry) has led groups to rethink the way their work, with good reason.

Woodcock refuses to see this: his recommendations are more surveillance and more anti-protest laws. Indeed, what he is also seeking is an end to unhelpful publicity about experiences of oppressive policing. Since “protest groups ascribing violence and brutality to the police multiplies the risk of confrontation”, he insists “mainstream actors should distance themselves from such unhelpful and potentially counterproductive behaviour” – rather than from police violence itself.

Regrettably, I suspect all this means he will absolutely hate the new resources Netpol is launching at solidarity.netpol.org

~ Kevin Blowe

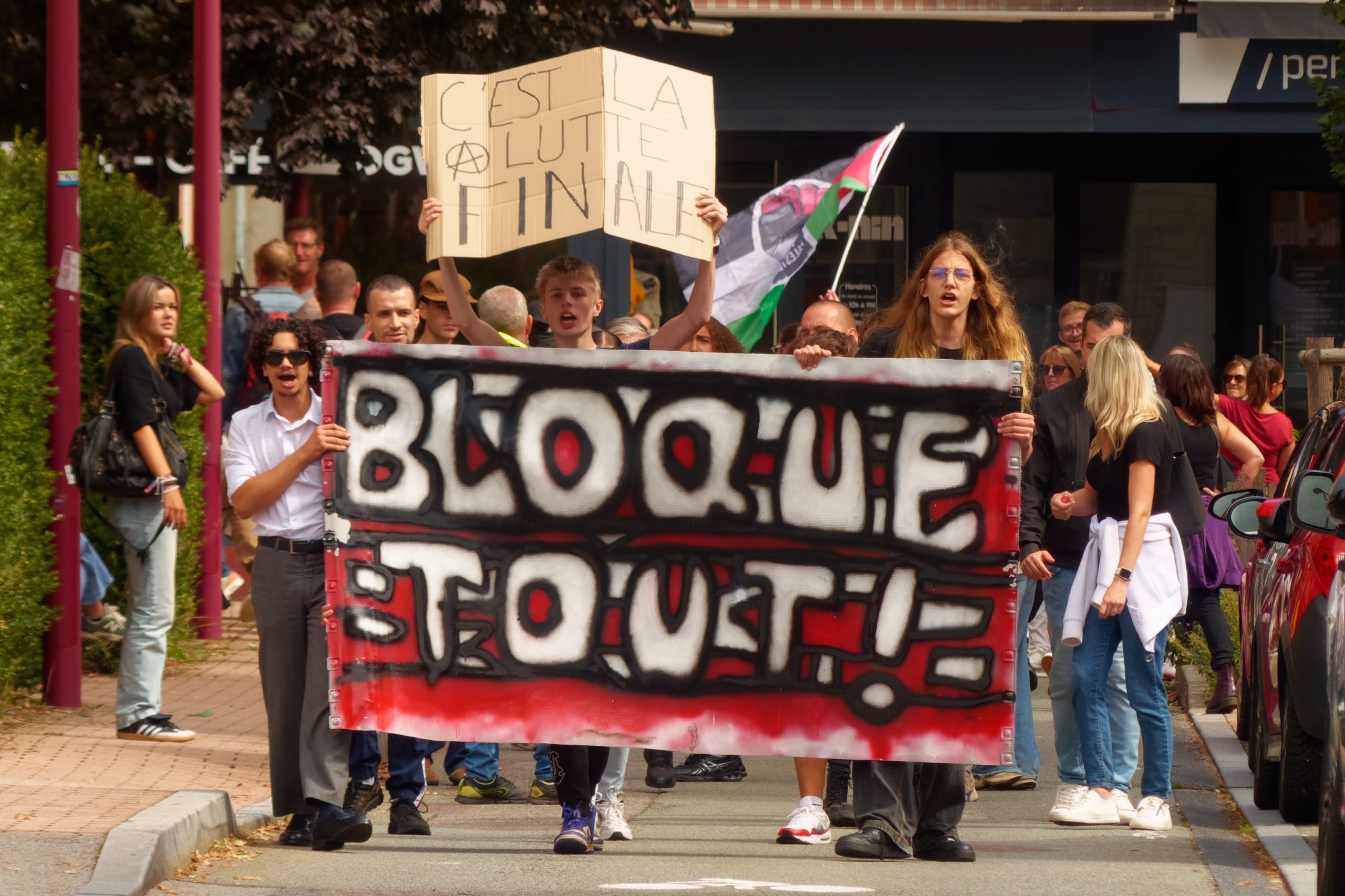

Photo: Alisdare Hickson