In part 2 of “On the practices of radical punk” we meet Abbie Hoffman and discuss Maximum Rock’n’Roll and the uses of Do-It Yourself culture

In the 1960s and 1970s, anarchist Abbie Hoffman was one of the founders of the Youth International Party, whose members called themselves “Yippies”. More than thirty years after his death, the United States and, more generally, those interested in the history of the counterculture, still see him as a symbol of the wind of freedom and protest that blew through American youth in those decades.

When Mark Fisher talks about the heyday of the counterculture and says that “What the capitalists were afraid of was that the working class would become hippies on a massive scale”, I like to think he’s thinking of Abbie Hoffman and the Yippies. I suspect he’s not referring to the beatniks we all too often think of today—a bunch of bell-bottomed sex maniacs who smoke pot and make out all day, doing acid highs in the city centre—but to agitators like the Youth International Party (YIP).

A libertarian party that emerged from the Free Speech Movement and the anti-war movements of the 1960s, the YIP claims to be more radical than its predecessors. Today, if we want to get a more precise idea of its practices, we can look at the written testimonies of the time, including Steal this book by Abbie Hoffman.

The book is divided into two parts: “Survive!” and “Fight!” In “Survive!”, the reader is treated to advice on how to steal, and conspire to get by, so as to depend as little as possible on money. Each sub-part is devoted to ways to get something without paying for it: food, clothing, furniture, transportation, land, housing, medical care, entertainment, all the way to “free money” and “free drugs”, before the catch-all “assorted free stuff”, itself divided into sub-parts—“laundry”, “pets”, “postage”, “veterans’ benefits”, “degrees”, and even “funerals”, where one learns how to “avoid the exorbitant price of death”.

The second part, “Fight!”, provides lots of advice on setting up a clandestine printing workshop, launching an underground newspaper, dressing up and causing havoc at a demonstration… Before discussing “popular chemistry” (or how to make stink bombs, smoke bombs, Molotov cocktails, Sterno bombs, aerosol bombs, pipe bombs, etc.), first aid, the use of “peacemakers” (rifles, shotguns, etc.), the “strategy of chaos” and finally “clandestinity” (or how to find false identity papers and go underground).

For the twenty-first century reader, what is striking in Steal This Book is the tangibility of the subject. Certainly, one of Hoffman’s particularities was to manipulate a humour that would not have been denied by agitators such as Dada, the surrealists, the situationists or the provos, to name only the most obvious. But it seems to me that it is thanks to his conviction of working for the common good, that is to say against capitalism, that Abbie Hoffman allows himself to manipulate this humour: if the goal is to move towards a more just society and to annihilate what oppresses us, and if this objective seems within reach, we can understand that the author wants to do it with joy, itself conducive to humour, and not with a defeatism that is too often counterproductive.

"Here, one learns how to make glue from toothpaste, how to make a shiv from a spoon, and how to establish complex communication networks. It is also here that one learns the only possible rehabilitation: hatred of oppression”. – Abbie Hoffman

Steal This Book was not written for posterity: it was a work intended to serve as a combat guide for fans of Janis Joplin, the Grateful Dead, Jimi Hendrix and the like, in their own present, that of the late 1960s and early 1970s in the United States. But then, why mention it today? And above all, nearly fifty years later, why did a French publisher undertake to translate it?

One answer is that Steal This Book is a historical document, that of a movement that did not survive the neoliberal counteroffensive of the 1980s. If most of Hoffman’s advice is no longer applicable, the contemporary reader is nonetheless struck by the liveliness of these pages… But also, and above all by their optimism, the same one that Mark Fisher evokes when he writes, in the second half of the 2010s, that “We must rediscover the optimism of the 1970s”.

It’s true, Steal This Book runs on the hopes of its generation – that of the Summer of Love, LSD, psychedelic music, Woodstock, but also of the free press, the fight for civil rights, the fight against the Vietnam War. This generation that Mark Fisher considers, in hindsight, to have represented “a serious danger” to the powers that be. Fifty years after its publication, the reader of Steal This Book is struck by the feeling that everything seemed possible at the time, and that nothing prevented anyone from deserting the wage system and organizsing themselves, alone or in affinity groups, to live differently, not tomorrow but here and now, while actively fighting the enemy, namely oppression in all its forms.

For me, Steal This Book brought up questions that had remained unanswered after reading Acid Communism. However, they are two very different texts: while Mark Fisher remains in theory, drawing inspiration from what he has read and heard a posteriori about the North American counterculture (as well as Italian autonomy in the 1960s and 1970s), Abbie Hoffman writes in the present tense and draws on his real-time experience, to describe to us what it is like to live the counterculture day by day. In other words, as different as they are, these two texts can also be read as two sides of the same coin: on Hoffman’s side, practice, on Fisher’s side, theory.

Personally, these two books reminded me of practices at work here and now, in underground music and autonomy circles. In particular, they remind me of what I have experienced for the past twenty years as a participant in radical punk. So I wonder if these practices are not modest, concrete and accessible illustrations of what Fisher hoped to see reborn at the beginning of the twenty-first century. And this is why I want to describe some of the ways in which radical punk seems to me to be a continuation of the counterculture as Hoffman showed it in Steal This Book , but also, perhaps, a prefiguration of the acid communism as Fisher tried to define it before his death.

On radical punk and DIY

“People should resist in whatever way they can. They should cooperate, try to create environments where they can maintain some form of sanity, and have fun doing it. If you feel trapped in that system, do what you can to fix it. Otherwise you will become bitter, and that will be a victory for them”. – Tim Yohannan

Before discussing radical punk media using the example of Maximum Rock’n’roll, let me throw a pebble in the pond: punk is not and has never been the opposite of the hippie. These are two figures from the same continuum, that of a counterculture that includes Dada as well as the provos, the surrealists, the lettrists and their situationist offspring, the Zapatistas, radical feminists, gay liberation movements, heretics and witches, armed struggle groups (Weather Underground, Black Panthers, Red Army Faction or Action Directe), homeless people, hobos or vagabonds, rappers, free-jazz and experimental musicians, party-goers, beat generation writers, skinheads and so on… Without forgetting, therefore, the hippie and his “nihilist double” punk.

If the mainstream media has always sold us a story opposing punks and hippies, those who take the time to look into it will find that the bridges between the decline of the hippie (from 1969) and the advent of punk (1976/1977) are numerous. The term “punk” was used from the beginning of the 1970s by certain journalists from Creem magazine, including Lester Bangs, to describe garage groups like the Stooges or the MC5. In New York, the Velvet Underground was formed in the mid-1960s and immediately distinguished itself from the hippie movement by the darkness of its music and its message. Not to mention the countless groups now called “proto-punks”, which also blur the boundary between the two periods: electric eels, David Peel & The Lower East Side, The Fugs, some garage bands from the Back From The Grave compilations, and so on. This theory is verified in the world of literature, comics, cinema, “politics” or at the level of individual testimony.

One such individual, Tim Yohannan, was born in the United States in 1945; twenty years later, he was caught in the full force of the psychedelic explosion. A 1968 photo shows him sitting in the desert with long hair, a moustache and sideburns; on Wikipedia, his biography states: “Yohannan was first a leftist of the counterculture of the 1960s, before applying what he had learned from it to the punk scene”.

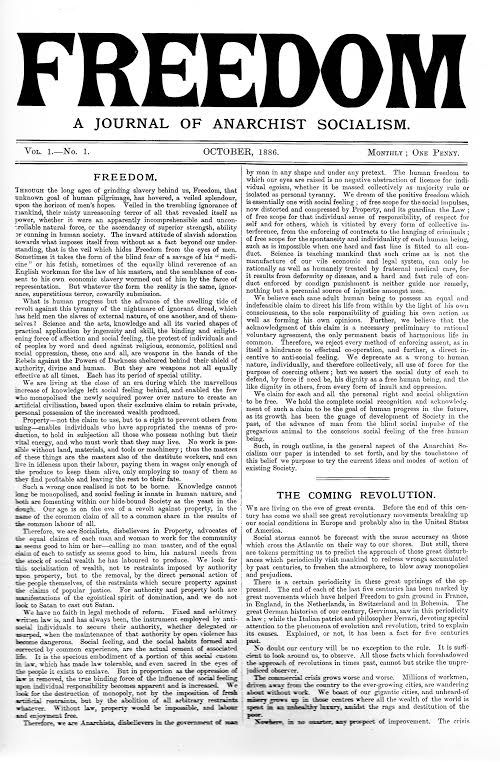

A self-proclaimed Marxist, a harsh critic of the commercialization of music, and a controversial figure due to his radical positions, the man nicknamed “Tim Yo” launched a punk show on the community radio station KPFA in Berkeley, California, in the late 1970s. He called it Maximum Rock’n’roll and surrounded himself with what he called his “gang” of DJs, including Jello Biafra, singer of the Dead Kennedys and future boss of the Alternative Tentacles label. But it was in 1982 that Maximum Rock’n’roll, while continuing to broadcast on KPFA and then on community radio stations throughout the United States, also became a fanzine of the same name, dedicated to the hardcore punk explosion then underway in the United States and around the world.

To sum up the state of mind of this punk Stakhanovite, and to understand how his thinking brings him closer to Mark Fisher or Abbie Hoffman, we will refer to his countless mood pieces and columns in Maximum Rock’n’roll, as well as to the interviews he gave before dying of cancer in 1998, at the age of 53:

“The major change I’ve seen in the last twenty years, I would say, is the way capitalism has developed, giving more and more power and wealth to a small number of people with the blessing of the media, which has affected the way people think. To me, it’s part of a strategy: bombarding people with so much information and so much bullshit that they don’t know what to think about anything. And it’s been very effective, in the sense that today, with the defeat of any alternative, capitalism reigns – until it destroys the world or destroys itself. I don’t think there’s any effective large-scale resistance that can be organized against the current power… Which is not to say that we shouldn’t fight. In other words, I don’t feel depressed by all this”.

From the moment the paper version of Maximum Rock’n’roll was launched, things moved very quickly: a myriad of hardcore punk bands were formed all over the world, and their members discovered, sometimes with amazement, the Marxist, libertarian and internationalist vision of Tim Yo and his gang. The cover of issue 6 (May-June 1983) is a good illustration of this: we see a live photo of The Dicks, these communist, transvestite and homosexual Texan punks, under the big headline “THE DICKS: A COMMIE FAGGOT BAND?!!?” .

Knowing that we are in the United States, where the term “communist” is often considered an insult, especially in the middle of the Reagan era, all in a hardcore scene already divided between reactionaries and progressives, the message is clear: choose your side, comrade. The editorial line of “MRR”, as its readers call it, will remain unchanged for the 37 years (!) of publication of the fanzine, which ceased offline publication in 2019.

The issues, sent to the printer at a bi-monthly then monthly rate, are all about a hundred pages long, on the cheapest newsprint so that the sale price remains affordable; the content consists of a mix of interviews and hardcore/punk/garage/post-punk columns, advertisements (but not for bands on major labels and their subdivisions), but also mood pieces (the famous “columns”) and a reader’s letter section where we debate politics and practices. The operation is collective, self-managed, without subsidies; everyone, including Tim Yo, is a volunteer; MRR runs on passion, and covers the punk scene like a new kind of proletariat, fighting against all the reactionaries in the world. In the middle of the Cold War, we find introductions to Eastern European punk, still under the Soviet yoke. This was the time when the radical punk network was being established, and MRR played a leading role in it, to the point of being nicknamed “the CIA” or “the political correctness police” by its detractors. To which the collective of volunteers, who encouraged punks from all over the world to submit articles, letters or interviews, invariably responded: “You don’t like what you read in MRR? Then take matters into your own hands and CONTRIBUTE!”

Fast forward, change of scenery. We are in France, nearly 10,000 kilometers from MRR HQ, in the early hours of the twenty-first century, eighteen years after the launch of the fanzine, and two years after the death of Tim Yo. As a testament, the latter wrote a copious guide explaining to his successors how to hold the MRR boat, if possible against all odds, since conflict is life. It is stipulated that the fanzine should never be printed on anything other than newsprint, that it should never be in colour, that bands signed to major labels will never be allowed to appear there… But also that to take on the role of “coordinator”, which had previously fallen to Tim Yo, it is better to favour women, since “in the punk scene, by force of circumstances, they are generally more combative than men.” And that’s how, on a sidewalk in a medium-sized town in France, a young homeless punk barely of age, with a mohawk on his head and a skateboard on his feet, an “A” circled in Tipp-Ex on his backpack, LSD all over his brain and black ink all over his fingers, found himself leafing through for the first time in his life a musical fanzine with a strong feminist tendency, coordinated for two years by a woman named Arwen Curry.

You probably understood: this young man was me. While I had just dropped out of school, slammed the door of my parents’ home, thrown my belongings into a backpack and hit the road, my predilection for English allowed me to discover the fanzine that would change my life. I already knew the name, often cited in interviews with punk groups; its creator himself was not completely foreign to me, since I listened to the decadent clowns of NOFX who, a year before Tim Yo’s death, recorded a scathing song mocking his legendary inflexibility.

What I don’t know yet is that one of the niches of Tim and his successors is to educate young punks, encouraging them to think for themselves, to challenge all forms of authority and to get their fingers out of their ass to launch musical projects – bands, fanzines, labels, venues, etc. For me, who grew up in a family without political culture, where we never talked about anything, and whose childhood friends were mainly interested in skateboarding and the naiads of Baywatch, the shock is enormous. Very quickly, I send a copy of Black Lung, my own fanzine – twelve A4 sheets written in BIC pen – like a message in a bottle, hoping without really believing that MRR will review it. Two months later, I received a yellow-orange envelope containing the latest issue which, oh joy, oh consecration, recommended my rag printed in 25 copies to French-speaking punks around the world – because MRR was still in its glory days, before the advent of the Internet, when the print run was in the tens of thousands of copies, distributed on press tables from Japan to Finland, from Australia to England, from Poland to France.

This contact led to others and, quite quickly, encouraged by the calls for contributions (“Come on, take matters into your own hands and CONTRIBUTE!”), I submitted an interview with a small hardcore punk band from Bordeaux, which was published shortly after. New shock: I was barely 20 years old, I worked in a factory, I only had a degree in the street, and here I was a journalist for a newspaper that Americans could find at their newsagents, and that punks from all over the world called their “bible”. While continuing to write my fanzines, whose editorial lines owed a lot to MRR, I contributed more and more to them, until I joined the collective and was offered a monthly column, which would first be called “Brain Works Slow” then “So Long, Neurons”. The coordinators who took over from Arwen Curry, Layla Gibbon at the head, also encouraged me to submit drawings to them, which always ended up being published, at a time when no one in France ever asked me for them. Little by little, all this helped to give me confidence in my “artistic practice”, me, the shy self-taught guy from the Parisian suburbs. Or to put it another way and use MRR vocabulary, this group of American women whose faces I didn’t even know largely contributed to my empowerment … Until I decided, in the early 2010s, to go and pay them a little visit in San Francisco.

More next week… The first part is available here

from Audimat via Lundi Matin, corrected machine translation