Jamie O’Brien tells his story of growing up surrounded by industry and injury in the Welsh steel town of Port Talbot…

November 8 2001. My grandfather had just brought me home from rugby training. Walking into the living room and seeing my mother’s parents there. The grave looks. Before a word is uttered it’s very clear something terrible has happened. Who’s died?

“Daddy has been in an accident”

I run to the toilet. I still remember screaming out loud to a God I thought was merciful. Asking Him why he’d let this happen. The Catholic faith that had been ever-present in my upbringing had delivered its first major betrayal. How does an eleven year old process this news? You don’t.

We got lucky. My father survived. Three men didn’t. It happened on a Thursday night. Me and my sister were not allowed to go to the hospital right away. I’ve seen the pictures since. Good call, mam. Allowed off school Friday but back in Monday. People ask how I am. I guess I mumbled “I’m ok” but I can’t remember. Teachers talk about what happened. I receive stares. A surreal feeling. I was never one for being centre of attention.

I pride myself on my memory but I can barely recall the next twelve months. In and out of hospital. Not being able to perceive the suffering he was going through but I remember the atmosphere. Grief. Loss. Intangible. Mourning for a time you’ve already forgotten.

The steelworks had gone from provider of sustenance to killing machine. I could see it outside my bedroom window. Every day, every night, never resting, not subject to circadian rhythms yet I can’t help but see it as a living entity. To my mind it’s always breathing. There’s no escape from it. For a while I keep the curtains closed. My awareness of it never ceases. I can block out the sight but not the sound. Still it breathes.

I only have secondhand knowledge of PTSD. I saw the terror in his eyes when he was startled. I was aware of how often he replayed the night in his head as if he was watching a recording.

“It should have been me. Why wasn’t it me?”

I can’t make sense of this. Of course I can’t. The years pass by. The injuries still very much visible. I wouldn’t wish burn injuries on my worst enemy. A protracted inquest. Incompetence. Neglect. Negligence. Imperatives of profit. Machine logics.

“Daddy’s on the news!”

The verdict comes in. Accidental Death. Disappointed. Disgusted. Justice indeed.

Life goes on but there’s a lack. It’s hard to remember how things were before this but they had to be different. We receive compensation. We move house. At least I no longer have to hear our neighbour beat his wife through the walls. At least we don’t have to worry about our other neighbour stealing our car (again). No more hearing the train tracks rattle as I try to sleep. Despite this I was resistant. Most of us hold affection for our first home.

I can no longer see the works. Still it breathes, but at least I don’t have to hear it now. Life becomes a lot more peaceful. Outwardly at least. I guess this is how middle class people live. A perverse form of social mobility. I pray before bed every night. It becomes a compulsion. Please keep my family safe, God. He was merciful last time so I guess I owe him my attention.

If you live in Port Talbot there’s a very good chance that at least one member of your family is currently or was previously employed in the steelworks. In the case of my family, almost every man in my immediate family has worked there. My grandfathers, my living uncles, and of course my father, have spent almost their entire working lives there. Stories about the works. Rants about the works. News about the works. It’s the common ground that links the men in my family together. Even if it’s the same story for the hundredth time, nobody will object to it being retold. There’s clearly a comfort in this shared experience. More of a unifying force than the familial ties in many regards.

Save Our Steel. More of a plea than a demand. Depending on who you are, it can be read as a death cry or a battle cry. We don’t need to look too far afield to point to what we want to be saved from. The consequences of defeat echo all around us. The ghosts of an industrial past are forcefully kept out of our industrial present. Through it all, it has remained. It’s all we’ve ever known.

Save Our Steel. How to personally relate to this? You may think of production. You may think of the workers. You may think of history. You may think of the uses of steel. You may think about identity. You may think it can be saved. You may think it cannot. You may welcome its demise. You may not be able to comprehend it.

Save Our Steel. When I think of ‘our steel’, I think of sulphur fumes. I think of smoke. I think of the coughing fits provoked by its proximity. I think of fire. I think of corporeality. I think of burned flesh. I think of death.

What once seemed incomprehensible seems possible if not inevitable. Melancholy for how things used to be soon give way to mourning for what will never return. To think of what comes next is difficult when you cannot accept what may be soon to go.

Michael Sheen ‘crucifying’ himself down the beach lamenting what had been lost may have been heavy on the symbolism but it expressed a truth that is felt throughout the town. Of course this isn’t exclusive to us. In comparison to the post-industrial towns that surrounds us, we’ve been relatively fortunate. However, the steady degradation of the world you know effectively contracts your horizon. To know others are worse off is merely a reminder that worse is to come.

As indelibly linked as the works is to my family, I feel like an outsider. I have never worked there. I will never work there. Through imposing a trauma on us that we could never have prepared for, the works allowed me to be the first one to go to university. It provided a financial comfort we would not have attained otherwise. In many ways, it may have saved my life. It still, however, remains fundamentally unknowable to me. My understanding, my stories, my images will always be secondhand.

If I am here to see it close down completely, I don’t know how I will feel. All I do know is that it will represent the destruction of a way of life that has shaped mine more than I can ever appreciate. Its history and its scars will be carried with us as long as we stick around. The works will never be far from the periphery of our thinking. It will remain a reference point for those who may have little else in common. Even when it no longer breathes, its presence will remain inescapable.

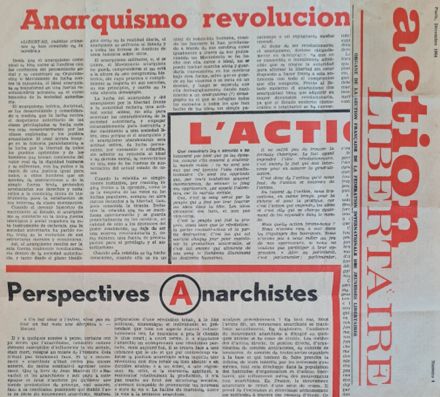

This article first appeared in base publication, which brought out its latest hardcopy late last week. You can read the magazine online at basepublication.org or pick up copies from radical outlets, including Freedom Bookshop and Housmans.