Maurice Reclus considers the problems with organising at firms which are heavily virtualised and sited across multiple countries.

I sat in as an observer at a social for Game Workers Unite the other day, an attempt to set up a union for the games development industry. It led to some interesting conversations about the difficulties involved with organising this aggressively anti-union sector, which I’ve been worrying away at in other contexts for a while.

The essential nature of games production is that it’s precarious, heavily subscribed, has no serious trade union presence in its history and takes advantage of the mobility of virtual production to atomise its workforce. The challenges of organising anything in that sort of atmosphere are therefore formidable and, it should be said, analogous to a great many other industries which the trade union movement has failed to seriously impact in the last few decades. Graphic design and online media (despite credible efforts by the NUJ) for example have remained for the most part union-short.

In an effort to work through some of the implications raised I’ve listed a few of the issues which cropped up.

A lack of existing trade union cultures

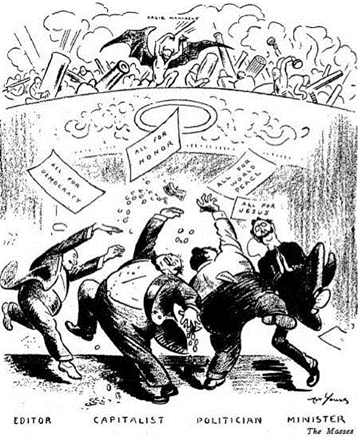

As with most sectors in “new tech,” gaming has little trade union background to draw on. What this means in practical terms is that the first task of any union organising effort is not simply to make people better organisers, but more often to explain what a union is. This is by no means a problem specific to gaming or tech, as any strike participant who’s had the “I really support what you’re doing” comment from people crossing their picket line can tell you, but it is particularly prevalent. The concept of unions as leverage against the untrammeled power of bosses, as opposed to offering merely legal insurance or a vehicle for protest, is hard to budge (particularly when so many TUC unions have fallen into offering that “service” model as standard).

And that’s merely the first stage of the problem. The second related factor is that in “old” industry (transport, manufacturing etc) there is a retained level of experience in the form of both shop floor activists (former and present) and in the bureaucracies of the unions themselves. This is not to be sniffed at in terms of growing new branches, as simply the ability to find out from an old hand what the likely dirty tricks will be is a massive help when trying to get recognised. The importance of this background knowledge has been heavily underlined by the experience of the syndicalist IWW union, which recently produced a startling membership graph:

It looks weird because it’s actually going up, which is almost unheard of in the third millennium. What happened in 2004 to start that spike? Well the main event that year was an organiser training system which got rolled out teaching new members — and anyone else who wanted to learn — about strategies for winning in the workplace. Concepts such as workplace mapping and inoculation are very common in traditional union organising but almost unheard of where unions have no existing base and basic training offered to all, such as that on offer from the Wobblies, can have a marked effect on success rates.

Multinational offices

This isn’t just a problem for gaming (and hasn’t been for some time) but continues to be a major issue for trade unions in general, particularly in disputes. One person I spoke to recently about games organising for example noted that their (relatively small) company had sites in the US, UK and eastern Europe, each with their own sets of issues, rights and requirements for taking legal industrial action. In the US there’s even differences across individual States, with some groups of workers being banned from striking entirely, while in the UK extraordinary amounts of notice is required before a legally protected action can take place. This is before any other issues around communication crop up.

This heavily favours bosses, who number so few and have so many resources that they can easily, using secure communications and savvy lawyers, organise individual legal challenges to say, the way in which the balloting was set up (a favourite in the UK). Their favourite tactic in multi-site disputes of divide and rule (collapse the action by leaning on the weakest branch) is especially effective when each unit is isolated in its own country. Traditional union escalation and solidarity-building tactics to win disputes such as focusing mass pickets, even where they’ve not been made illegal (UK again), are rendered impossible by physical distance, and while direct communication over what’s going on is possible it’s in no way as effective when limited to a Skype call or, when physically sending a delegate, costs a month’s wages.

Gaming is particularly vulnerable in this regard because not only is it frequently multi-national in its production approach, it’s also heavily virtualised and, often as not, it’s entirely possible to run an office remotely for extended periods of time. In theory this makes it nearly impossible to enforce a picket line — not only would there be no gate to close, but scabs and blacklegs could be entirely anonymised.

Finding a solution for this is something the TUC unions have failed to do for years, though this is not (for once) something to be entirely blamed on hideous levels of bureaucracy and uninspired full-timers. They have no base in new tech, meaning they don’t understand the specific challenges and have limited means to get in with a primarily younger workforce.

That’s not to say other forms of leverage can’t be found. Chaos is never far away at any given games firm. Production is notoriously full of potentially fatal bugs even when people are working at their best, let alone when they’ve been forced to do vast amounts of overtime or are facing contract trouble. A folder of important files misplaced, the latest version of the game accidentally uploaded publicly rather than privately … such slip-ups happen when people are tired and impoverished, and can serve to focus a boss’s mind. In an industry where crunch time is the norm, a spate of sickness from people near the end of the development cycle, where there’s little hope of bringing in workers from scratch, can cause untold difficulties for publishers.

But producing results with collective action is something needing careful thought in this different frontier, and relies on an atmosphere of solidarity which is currently far from assured.

Communications

This is the big one. Personally I have had enormous trouble on occasion explaining the dangers of front-facing trade unionism in the internet age to older activists, who often still work on the principle of openness and the use of real names as “hiding” undermines the sense that trade unionism is legal and above board.

The problem of course is that yes, there is a strong case for this in the cause of persuading people they have nothing to be scared of in joining a union — but tech is not that kind of atmosphere. The essential problem is as follows:

- Gaming is founded on short-form contract work so people move company a lot

- Gaming is aggressively anti-union

- Announcing yourself as a trade unionist online, or even discussing it, will leave a trace

- When hiring, bosses can and will Google your ass

- When your name comes up linked to the union, bye bye job

Note, at no point have you done anything wrong and at no point has any boss done anything so crass as dip into an illegal industry blacklist. All that has happened in this scenario is that you’ve been publicly linked to trade unionism, which is something tech bosses currently crack down on by default. Pressing in this context is to achieve a cultural shift, so that the untraceable victimisation of people simply for being trade unionists ceases to be an industry standard. The key is a situation where union membership becomes normal.

Meanwhile at the office, in-house communications are always controlled and monitored by management, particularly anything moving between countries. As an organiser then you can physically talk to people who you trust, but you can’t of course automatically trust randoms in the US or eastern Europe office, whose co-operation you’ll need to pose any kind of united front. Which means, especially if organising with others into a union, online communications will have to be anonymous (otherwise it’ll be screenshots of your complaints followed shortly after by “sorry we’re going to have to let you go). And at this point, if a dispute arises you’ll have to assume that the boss themselves is on that anonymous server, because it only takes one stoolie to hand over the details.

So already this is a complex dance, invidious to more militant organisational tactics and off-putting to recruitment “maybes”.

What to do?

Given the above, there appears to be two main possibilities.

- Persuade a critical mass of people in the industry that trade union membership is not de facto something to fear, and focus on getting it normalised. Get more progressive-minded companies to sign up welcoming union membership noting that unionised workplaces actively bring significant benefits through better-understood working dynamics, higher morale, less job churn etc.

- Take the direct route of forcing recognition, in which case there needs to be a strongly clandestine element to organising from the start, and a strategy which incorporates an awareness of how to beat not just traditional union-busting methods but the particular circumstances of tech-industry working practices.

The GWU is, largely, pitching the former approach, though not doubt with the proviso that initially its members won’t be putting details online for dodgy bosses to misuse:

and much as I’d personally welcome something which kicks the doors down to make bosses behave in less poisonous ways, I can see the logic of getting at least some shops opened so that the idea of a union becomes less outlandish. And even from the perspective of bosses, the trade union movement does have a lot to offer. It can’t have escaped the notice of some of the industry’s more thoughtful top brass that burnout and job churn are such a shit-show.

However things turn out, it’s an interesting project which raises important questions and I wish GWU the best.

Maurice Reclus