First produced in 1886, the monthly British anarchist newspaper Freedom has ceased print publication with the second edition of 2014, after the Freedom bookshop collective concluded that “a sold hardcopy newspaper is no longer a viable means of promoting the anarchist message”. Freedom will become an online publication, supplemented by an occasional print newssheet.

The raw facts underpinning the editors’ decision are pretty incontestable. The numbers of paying subscribers has slid to 225, and the paper is now dispatched to fewer than 30 retail outlets nationally. The annual financial shortfall the paper is saddled with is £3,500 (compounded each year, naturally), and that figures leaves out the effective £10,000 solidarity subsidy provided through the under-charging by printers Aldgate Press.

The editors have taken the only realistic option open to them, and anyone in the movement attacking them for taking the decision needs to respond not with criticism but with a detailed plan showing how the paper could immediately triple direct circulation, quadruple wholesale distribution and generate an additional £20k income a year. It is a dispiriting position to find yourself in, but the editorial collective has made the necessary tough call.

Over the last ten or so years, Freedom has published a number of my reports, news stories and reviews on different aspects of the history of the anarcho-punk movement (amongst other things). I’m grateful for that, and pleased to have been able to write for and support the paper.

Freedom occupies a special place in my anarchist heart, because it was the first anarchist newspaper that I ever picked up, in 1980 at the age of 17; a key part of the process of deciding that I would become a member of what I hoped would soon evolve into the mass, Thatcher-toppling ranks of an unstoppable British Anarchist Movement. And, yes, like many participants in political activism, I archived even from a young age. I still have the earliest issues of Freedom that I read – kept in the box marked ‘Freedom: 1980-1982’, stacked alongside numerous descendants, and stored in chronological order.

As I read those first few issues back then, a lot of the paper’s frame of reference was pretty alien to me. The lyrics and wraparound essays of a Poison Girls or Crass twelve-inch record had more immediate anarchist resonance for me, than much of what appeared to be (from my teenage punk perspective) the frequently strange and arcane political and cultural preoccupations of Freedom’s writers. (I have a rather more tolerant [and a little bit better informed] view of what I saw as incomprehensible pieces of radical journalism looking back today.)

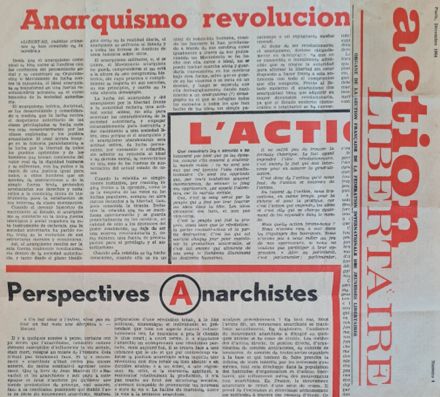

But there was no doubting my affinity with the sentiments and aspirations which I saw motivating the paper. As I also discovered Black Flag, Xtra! and Anarchy, the range of the expanding anarchist press seemed (alongside the stacks of punk fanzines piling up in my room) to be an even more encouraging sign. The anarchist movement appeared to be multiplying. I was initially rather nonplussed by the sometimes venomous and toxic terms with which Black Flag would denounce “the political idiocies” of Freedom (and vice versa), and wondered, with endearing naivety, if it might not be better if we anarchists just all ‘got along’? (years later, I’m clear on the need for continuous rigorous, sharp political debate, but have near-zero-tolerance for the corrosive, self-destructive role played by organisational sectarianism; however expressed, and whoever expressed by).

Like pretty much all libertarian publications (published without paid staff and on a logistical shoestring) Freedom was vulnerable to wild lurches of political position as editorial collectives fell out, dissolved or were rejuvenated by incoming volunteers – often joining in order push the paper in a particular new direction. In the early 1980s, Freedom was broadly sympathetic to the anarchist-punk movement, covering the establishment of the Anarchy Centre in London, the anti-Falklands War protests, the Stop the City initiative and (in the level of detail only surpassed by Peace News) the radical wing of the anti-nuclear movement in the UK and right across Europe. Freedom also played an unrivalled role in publicising the activities of the growing numbers of local anarchist groups kick-started by an upsurge in punk-inspired activism.

In 1982, Freedom even gave its front cover over to the launch of the anti-war Wargasm benefit compilation album (which featured a variety of punk artists – anarchist and otherwise): not something any other contemporary anarchist publication outside the fanzine world was likely to do. There were other cross-overs too. Crass’s statements and press releases were published. Over the next couple of years, the anarchist graphic artist Nick Lant, whose signature work featured on the album and single artwork of many Subhumans releases, regularly contributed striking artwork to Freedom, producing some memorable covers in the process.

Throughout this time, as my own activism took me around the country, I would pick up the latest issues from one of the still-sizeable networks of radical and alternative bookshops dotted around the country, or from one of paper’s street-sellers at a demonstration or march. By this point, my unbridled expectations of the forward march of anarchism in the UK had been tempered somewhat, and I had a more realistic sense of the circulation, readership and impact of anarchist journalism. (I remember being dismayed by the size of the piles of unsold Black Flags stacked in the back room of the 121 Bookshop in Railton Road, Brixton on a visit in the early 1980s).

Over the next twenty years, even as I co-edited fanzines and anarchist and libertarian publications myself, Freedom remained, for me, an essential publication. Just as likely to exasperate and outrage as it would be to inspire and inform, Freedom rarely lack personality. The paper flipped between different formats, moving to traditional ‘newspaper’ size, back to A4 magazine shape, then to a short-lived A4/A3 ‘combo’ (which gave it two front covers, depending on which way you unfolded it), and then back to A4. The paper experimented with different mastheads, fonts and page layouts.

My personal favourite was the eight-page newspaper format launched with the first January issue of 1983 (which I remember I bought from Birmingham’s Other Bookshop). It was a bold, strong, five-column monochrome agit-press design. Striking to look at, and easy-to-read, it also allowed space for illustrations to breathe. Design-wise it looked like a confident and convincing anarchist paper. Around this time, the reach, range and quality of contributions was stepped up too, as the paper’s collective sought to raise editorial expectations. The group acknowledged: “Too often in the past, we have had to print poor material just to fill the paper to get it to press in time. We neither like this state or affairs nor wish it to continue.” The editors also hoped that the new format would “be more likely to interest people, to take them beyond the newsagents’ shelves and into its pages”. Within a couple of years, the format changed again; in another attempt to make the medium better match the message.

In response to criticism that it was too much of a ‘London-centric’ paper, plans were drawn up in the mid-1980s to rotate editorship around the country between issues. It was what might be called ‘an ambitious plan’, but after some brief feasibility checks the idea was shelved. As it had several times in the 1970s, the paper set itself different publication schedules, moving between weekly, fortnightly and monthly production patterns (and sometimes struggled to meet each of these unforgiving targets). But none of these reinventions transformed the levels of readership or circulation. That would have required the active efforts of a growing network of supporters and advocates.

And yet while papers such as Class War burned bright for a while; or, like the publications of the Anarchist Workers Group, barely saw the light of day before disappearing, Freedom possessed the resources and the resilience. In 1986, its commemorative publication Freedom: A Hundred Years reaffirmed its incontestable claim to be the longest running anarchist newspaper in Britain (and, also, how its esoteric political interests were as irrepressible as its determination to continue publishing).

When I could afford it, I took out a subscription, and then later I decided that I should write for Freedom as well (judging that a couple of intemperate contributions to the Letters page in 1982 really didn’t count as ‘helping out’). As different editors came and went, contributing to Freedom could be an unpredictable experience. In the analogue, pre-internet years, it was just as likely that your postal contribution to the paper would disappear without trace (never to be heard of again) as it was to be published (unaltered and word-for-word) in the next issue.

Then there was that time more than a decade ago that the editors re-wrote one of my articles so cack-handedly that, when they published it above my name, it expressed political ideas that I did not hold. Then there was that other time, a couple of years later, when the editors re-wrote one of my articles so cack-handedly that it… no, wait… that was actually quite a lot like the previous experience. But most times, Freedom’s editors were skilled, supportive and encouraging (and, OK, on occasion still desperate for usable copy!).

There was a point during the 1990s that I became so exasperated by the paper’s slide into the realms of other-worldly detachment (another editorial redirection into unhelpful territory) that I opted not to renew my subscription. But after a few years of picking up issues every time I visited Housmans bookshop in London or News from Nowhere in Liverpool, it was clear that Freedom had reconnected with the real-world of radical political activism. I recanted and re-subscribed; renewing each year until the final print issue arrived on my doormat last week.

There have been periods in the history of the paper when it largely reflected the perspectives of a particular current within the anarchist tradition. As the editors also acknowledge, Freedom has continued to pay the price of its previous partisan practice, noting that the paper has “not managed to shake the legacy of the past and get different groups to back it as a collective project”. Like its anarchist rivals, its treatment of its political opponents could, at times, be sour and overly-judgemental. Historically, certain prominent figures around the paper exerted too much influence over the operations of Freedom Press, and resources not always directed to the most fruitful of ends. (The Raven? You might say that. I couldn’t possibly comment.) But in more recent times, as Freedom has consciously re-positioned itself as an open, accessible journal of the anarchist movement and “a resource for anarchism as a whole” (albeit reflecting the predominance of revolutionary class-based anarchism within the culture) these criticisms have lost any purchase.

Radical movements always attract more than their fair share of “eccentrics” with the axes to grind, and Freedom has never lacked the attention of the oddballs who demand ‘that their 20,000 word critique of the anarchist movement be published in full in the next issue, or the collective must resign and face a political trial’ (I’m paraphrasing, but regular Freedom readers will recognise the style from the Letters page). However, the numbers of those doubting Freedom’s openness and lack of sectarianism has thankfully dwindled. That the increasing respect for Freedom and Freedom Press within the movement (made more visible during the response to the arson attack on 84b Whitechapel High Street in 2013) has not translated into a tangible growth in writers, subscribers, supporters and sellers is both telling and disappointing.

Libertarian and radical movements often fail to treat their “house publications” well. Parties of the political far-left and far-right impose levies on members, expect supporters to fund, subscribe to and hawk the organisation’s publications. Full-time staff members are paid to produce the party’s rag (and then self-exploit by working ridiculous hours for low-pay for their employer’s political profit). Most such papers survive only on extensive subsidy, few reach credible circulation levels, and many burn up far too many resources (and are only kept afloat to sustain the over-inflated self-image of their party). There’s little in such a production model that anarchists would seek to emulate. It is nonetheless true that anarchist voluntarism falls short when there are too few volunteers.

It is notable that while the Anarchist Bookfair committee in London each year seeks larger premises to accommodate the growing number of attendees at what has become a landmark event in the movement calendar, the movement’s longest-serving publication gives up on print production in its 128th year due to an unsustainable lack of interest.

Some will insist that in the early twenty-first century, digital publication must be the norm and print production is becoming a costly anachronism (especially for short-run, ‘fringe’ publications). Freedom’s shift to the web, in this view, is simply a technological realignment; unremarkable and unavoidable. But that view misses the wider point that Freedom has been compelled to move entirely online (even discounting the option for a combined print and electronic existence) because too few members of the anarchist movement show enough interest in supporting the paper. What the paper collective openly recognise as the “lack of capacity to sustain it”. And it fails to acknowledge this change removes any opportunity to use the physical publication as an agitational and propaganda tool in the face-to-face encounters of “flesh space”: at the demonstration, on the picket-line, at the gig or in the pub.

It also implies that electronic-only publication is a win-win option: reducing production costs and opening up access to a global online readership. In truth, there’s a great risk that, if the new online Freedom does not attract sufficient interest from writers and web site visitors, it will wither and stall online: a fate which has met many small publications that have followed a similar print-to-web trajectory. This outcome has to be avoided.

The work of anarchist publishers, including Freedom Press itself, PM Press, AK Press and others does give greater cause for optimism; but the current picture of anarchist print journalism in the UK is distinctly patchy. Of the other anarchist publications I encountered as a surly youth: Anarchy has long since ceased publication; Xtra! only lasted a few issues; and Class War is gone. Direct Action (paper of the Solidarity Federation, previously the Direct Action Movement) enjoyed a brief period as an excellent journal of anarchist industrial reportage in the late 1980s, when edited out of Manchester. In the same period, Black Flag battled to occupy the space between the sober industrialism of Direct Action and the lurid adventurism of Class War, and was doggedly successful in the endeavour (in relative terms) for a time. I wrote and (in the pre-digital era, where cameras on demonstrations where few in number) took photographs for both publications; and for Virus, Organise!, Tyneside Syndicalist, Anarchist Times and several others.

Later shifting to magazine format, both Black Flag and Direct Action are today fitful and irregular publications, enduring long gaps between each this-could-be-the-last issue. The Anarchist Federation (previously the Anarchist Communist Federation) has been more somewhat more successful, with its now combined print-and-electronic versions of Organise! (theoretical journal) and Resistance (agitational paper); perhaps suggesting that having an organisational base behind anarchist publications is a requisite for long-term survival. However, the problems experienced by the SolFed in sustaining Direct Action imply that the issue is not that simple.

I’m pleased that – by a happenstance of timing – I was able to contribute to the final** print issue of Freedom, and I intend to continue writing for the paper’s new online edition. But while the decision to ‘go e-only’ is based on sound and realistic calculations, the end of Freedom’s life as a print publication is hardly a ringing endorsement of the ‘vitality’ of the current British anarchist movement.

That said, I don’t regret for one moment furtively pulling that first issue of Freedom down from the magazine rack nearly 35 years ago, immediately impressed by its assertion that it was an ‘anarchist fortnightly’. One statement in that first issue did immediately speak to my anarcho-punk worldview: “The social revolution”, it declared, “can only be built by people taking control of their own lives, asserting their independence, their rejection of the state, or power politics, or authoritarian lifestyles and the competitive values of consumerism forced on us from birth to death. […] We must reject and resist this inexorable erosion of our humanity and hopes with whatever means are available to us.” Sentiments that (for all their uncertainty about the dynamics and class struggle and the drivers of state power) would not have looked out of place on a Crass or Poison Girls handout. I’m sure that the inclusion of such ideas would have encouraged me to buy the next issue.

Millions of anarchist words have been printed in the decades since that aspiration appeared, as different currents within the movement have risen and receded. My own political perspectives have changed significantly since those halcyon anarcho-punk days. But it’s a sad thought that future issues of Freedom won’t be running off the press at Aldgate, reflecting the latest debates animating the anarchist conspiracy – through the imprint of black ink on crisp white paper. I’ll miss the tactile experience. But, to reappropriate the words of one infamous 1980s politician: ‘there is no alternative’. Here’s to the electronic anarchist future. Freedom is dead. Long live Freedom.

** There will be a final-final one-off Freedom being produced for the Anarchist Bookfair in the autumn.